By Robin N. Baydurcan

Michael Jeffrey Jordan v. China Trademark Review and Adjudication Board, with the third party QIAODAN Sports Company, Supreme People’s Court 2016

In December 2016, former Chicago Bulls basketball phenom Michael Jordan obtained an unprecedented victory in cancelling several third-party registrations for “Jordan” in Chinese characters, despite not owning any registrations for that mark. The success was only partial, however, as many of the target’s other objectionable filings were allowed to remain registered.

Michael Jordan’s surname can be represented by the simplified Chinese characters “乔丹,”—“Qiaodan” in Latin characters, pronounced “chee-ow dan”, a widely-used transliteration of the English name “Jordan.” Despite the local recognition of “乔丹” as the Chinese equivalent of “Jordan,” and despite Mr. Jordan’s fame in basketball-obsessed China, Mr. Jordan did not seek to register the Chinese version of his surname as a trademark.

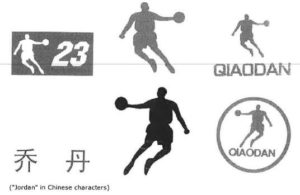

In the early 2000s, Qiaodan Sports Co. Ltd., a Chinese sportswear company, started using “乔丹” and “Qiaodan” to market its products. The company filed trademark applications for “乔丹” by itself and with a silhouette of a basketball player in mid-leap, a “Jumpman” pose made famous by Mr. Jordan in connection with the Air Jordan line of sneakers made by Nike. Qiaodan Sports’ applications eventually achieved registration and covered clothing, swimwear, footwear, and other goods. During the first decade of the 2000s, Qiaodan Sports registered nearly eighty trademarks in China pertaining to “Air Jordan” branding, including the following “Jumpman-esque” logo:

Over the years, the company became quite successful, owning more than 5,000 stores in China by 2015 and with annual sales that year totaling approximately US $500 million. The company’s products include basketball shoes and jerseys.

In October 2012, Mr. Jordan filed an invalidation action before China’s Trademark Review and Adjudication Board (“TRAB”), arguing that “乔丹” was a well-known mark associated with Mr. Jordan and his brand, and that Qiaodan Sports had filed in bad faith. This action was rejected by the TRAB and by the Beijing No. 1 Intermediate Court, based in part on the finding that the public would not necessarily draw a connection between the registered mark and Mr. Jordan specifically. As for bad faith, the tribunals seemed to disregard the fact that Qiaodan Sports had also filed for marks containing “23”—Mr. Jordan’s Chicago Bulls jersey number—and for marks containing the names of Mr. Jordan’s sons, Jeffrey and Marcus.

Mr. Jordan finally appealed to the Beijing High Court, the highest court in China, which ruled on December 8, 2016 that certain of Qiaodan Sports’ trademark registrations for “乔丹” with “Jumpman-esque” logo are invalid. In doing so, the Court relied on Article 31 of China’s trademark law, which pertains generally to “prior rights” as discussed further below. However, the Court allowed Qiaodan Sports to retain its QIAODAN word mark registrations on the ground that this term is a transliteration that can be represented by various combinations of Chinese characters, and not just “乔丹.” In other words, it was not proven that QIAODAN would be associated with Mr. Jordan specifically.

Due to the sheer number of Air Jordan-related trademark registrations owned by Qiaodan Sports, Mr. Jordan ultimately had filed more than sixty separate invalidation actions. Ten cases were heard by the Beijing High Court (it appears the others were time-barred, as invalidation actions must be filed within five years of registration), and Mr. Jordan won three of those (pertaining to “乔丹” and “Jumpman” marks) and lost the other seven (pertaining to QIAODAN marks).

In the cases which Mr. Jordan won, the Court recognized Qiaodan Sports’ bad faith and a “prior right” owned by Mr. Jordan, namely, his personal name right. The Court also held that the protection of a person’s name also extends to non-Chinese individuals, so long as the name is well-known in China and is used to refer to that specific person among the relevant public in China. There need not be an exclusive correlation between the surname and the individual, so long as there is a consistent correlation. The Court also recognized that Mr. Jordan is well-known in China; this conclusion was supported by the evidence, including Mr. Jordan’s visit to China in 2015 that received widespread media attention; two surveys showing that consumers would immediately associate “乔丹” with Mr. Jordan; and a large number of media articles about Mr. Jordan that were circulated in China over the years. The Court also noted that Mr. Jordan has an influence not just in sports, but in other industries as well; this increases the likelihood that Qiaodan Sports’ use of “Jordan” in Chinese characters would mislead consumers into believing there is a connection between the two parties. It is also important that Mr. Jordan established his fame in China starting around 1984, long before Qiaodan Sports filed its first objectionable trademark application.

These cases demonstrate the importance of registering Chinese-language trademarks and transliterations, particularly in the context of personal names and surnames. While Mr. Jordan ultimately won some of these cases based on an unregistered personal name right—which is seen as a significant win in registration-based China—his battle would have been much easier (and less costly) had he registered his name in Chinese characters years ago. And, his success before the Court was largely due to his demonstrable fame in China dating back several decades, which is an enviable fact that other individuals and companies litigating trademark disputes in the Chinese courts may not be able to prove. In fact, some commentators believe the Court’s recognition of bad faith in these cases was driven mainly by the high degree of celebrity enjoyed by Mr. Jordan, not to mention the media scrutiny preceding the issuance of these decisions.

Overall, the Michael Jordan case can be viewed as a positive “blip” on the radar screen of trademark piracy in China, and it is likely that true change in the regime will come slowly. That said, brand owners engaged in invalidation actions involving bad-faith filings and/or personal name rights are encouraged to submit this High Court decision in support of their own cases (the decision is not binding on other courts, but is likely to be persuasive).

It is also noted that following its issuance of the Qiaodan decision, the Beijing High Court issued a judicial interpretation stating that trademark applications for the names of “public figures in fields such as politics, economics, culture, religion and ethnic affairs” are forbidden under Article 10, which concerns signs that are detrimental to socialist morals or that cause “unhealthy social influences.” The Qiaodan decision was actually based on Article 31 (prior rights), as Mr. Jordan’s Article 10 argument was rejected by the Beijing High Court. Some commentators have suggested that the Court’s recent interpretation of Article 10 is unrelated to the Michael Jordan case, and that determining who is a “public figure” will still turn on establishing a link between the name and the celebrity. Indeed, the Court’s interpretation provides no guidance on how to determine whether the claimant is a “public figure,” thus leaving this task to the lower courts.