Christian Louboutin v. Van Haren Schoenen B.V., Court of Justice of the European Union, No. C-163/16 (June 12, 2018).

Christian Louboutin was once again victorious in an effort to enforce international trademark rights in his famous red sole. In its June decision, the Grand Chamber of the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) upheld Louboutin’s Benelux trademark registration for the red sole in an infringement action against competitor Van Haren Schoenen (“Van Haren”).

The dispute arose in 2012 after Van Haren began marketing red-soled high heels under its “5th Avenue Halle Berry” line. Louboutin filed an infringement action in the District Court of The Hague against Van Haren in 2013. Van Haren counterclaimed by arguing that Louboutin’s red sole was inherently unprotectable as a trademark.

Article 3(i)(e)(iii) of EU Directive 2008/95 prohibits registration of “signs which consist exclusively of . . . the shape which gives substantial value to the goods.” The prohibition aims to prevent trademark applicants from registering publicly-utilized designs much in the same way that U.S. law prohibits registration of functional marks. A registration for a functional mark may stifle competition by granting monopoly protection over a useful design feature that competitors might need in designing their own products.

In this regard, Van Haren argued that Louboutin’s Benelux registration violated Article 3 by granting protection for a shape which was a necessary design feature of the shoes. Article 3 gives no explanation of the meaning of “shape” in its proscription. The District Court of The Hague therefore stayed proceedings and posed the following question to the CJEU: “Is the notion of ‘shape’” . . . limited to the three-dimensional properties of the goods, such as their contours, measurements and volume (expressed three-dimensionally), or does it include other (non-three-dimensional) properties of the goods, such as their colour?”

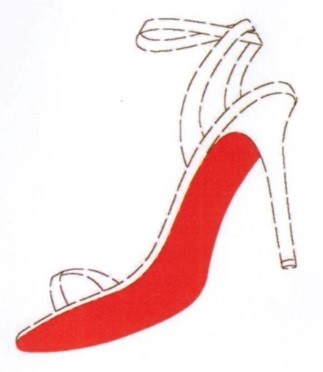

Louboutin’s registration described the red sole mark as consisting of “the colour red (Pantone 18-1663TP) applied to the sole of a shoe as shown (the contour of the shoe is not part of the trade mark but is intended to show the positioning of the mark).” The registered drawing is shown here:

Louboutin therefore argued that the mark does not include the shape of the heel’s sole, but simply the position of the color red on the sole.

The CJEU agreed. “[I]t cannot, however, be held that a sign consists of that shape in the case where the registration of the mark did not seek to protect that shape but sought solely to protect the application of a colour to a specific part of that product.” In other words, the registration does not seek to protect the shape of the sole. It seeks only to protect the famous red color applied to the sole.

The CJEU answered the District Court’s question by holding that “the concept of ‘shape’ is usually understood as a set of lines or contours that outline the product concerned.” It does not follow, the Court reasoned, that a color in itself, without an identified outline in the registration, can constitute a “shape.” Despite explicitly finding the meaning of “shape” within the context of trademark law, the CJEU claimed to interpret the term according to “everyday language.”

Louboutin’s victory before the CJEU confirms that color alone can operate as an inherently-protectable trademark, a controversial proposition to some. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit similarly held in 2012 that Louboutin’s red sole trademark was validly registered with acquired secondary meaning. Both decisions reinforce the general principle that any mark that operates as a source identifier can and should be registered and is enforceable, with some limitations. In this regard, the CJEU noted that most of the high-heel wearing population understands that a red sole exclusively identifies Christian Louboutin. Finding that the Article 3 limitations do not apply, the CJEU decision allows Louboutin to protect the goodwill he has developed since he first began marketing the red sole heels in 1993.

But Louboutin has not enjoyed unfettered protection. In the same case before the Second Circuit, the Court nevertheless allowed fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent (“YSL”) to continue marketing its “monochrome” red-soled heels. The Second Circuit reasoned that the contrast between Louboutin’s red sole and the rest of the shoe distinguished his products from YSL’s single-colored shoes, even if that one color was red. Louboutin was hit with a harder blow in 2017 when the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland denied Louboutin trademark protection outright. The Swiss Court considered the red sole design merely an aesthetic element of a “commonplace” design.

These conflicting decisions demonstrate the hurdles that today’s fashion designers face when protecting their intellectual property rights all over the world. Different approaches to similar questions across jurisdictions make consistent international trademark enforcement difficult. The CJEU’s interpretation of Article 3 follows a trend toward stronger intellectual property protection for fashion brands. However, Article 3 has since been amended by Directive 2015/2424. It now prohibits the registration of marks consisting of “the shape, or another characteristic, which gives substantial value to the goods.” How exactly this new law will be applied in the EU with respect to fashion brands remains to be seen.

The June decision also demonstrates the importance of thoughtful trademark prosecution. The CJEU noted that “the description of that mark explicitly states that the contour of the shoe does not form part of the mark and is intended purely to show the positioning of the red colour covered by the registration.” Had the prosecution attorneys not carefully identified the mark in positional fashion, this case may have gone the other way.