By Julia Belagorudsky

I. INTRODUCTION

While trademark protection is most commonly associated with source identifiers such as individual words, logos, slogans and a combination of these elements, trademark protection in the United States can also extend to colors, sounds, smells, and other non-traditional source identifiers. Brands appeal to consumers in varied ways, and trademark protection is often available for many types of consumer marketing efforts that are not immediately thought of as a trademark. Diageo, for example, has registered the purple and gold pouch bag that houses Crown Royal Whisky. The registration, which successfully claims acquired distinctiveness, describes the mark as a “three dimensional design of a purple cloth pouch bag with gold stitching and drawstring” and claims the colors purple and gold as a feature of the mark.

U.S. Reg. No. 3,137,914

The Lanham Act, the primary federal trademark statue in the United States, defines a trademark (and service mark) broadly enough that it can theoretically be anything that can be perceived by a consumer’s five senses, and that can be used to identify and distinguish the source of the goods/services. 15 U.S.C. § 1127.

The term “trademark” includes any word, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof –

- used by a person, or

- which a person has a bona fide intention to use in commerce and applies to register on the principal register established by this chapter,

to identify and distinguish his or her goods, including a unique product, from those manufactured or sold by others and to indicate the source of the goods, even if that source is unknown. Id.

There are, however, several unique hurdles to clear in order to register a non-traditional trademark. The mark cannot be functional (an absolute bar to registration) and if the mark is not inherently distinctive (a color mark for example), it must have acquired distinctiveness in order to be registered on the Principal Register.

II. FUNCTIONALITY DOCTRINE

A. Purpose of the functionality doctrine

The functionality doctrine is intended to preclude a business from monopolizing a useful product feature under the guise of identifying the feature as the source of the product. The Supreme Court of the United States has explained that, “[i]n general terms, a product feature is functional, and cannot serve as a trademark, if it essential to the use or purpose of the article or if it affects the cost of quality of the articles, that is, if exclusive use of the feature would put competitors at a significant non reputation related disadvantage.” See Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 U.S. 159, 165, 34 U.S.P.Q.2d 1161, 1163-64 (1995), quoting Inwood Labs., Inc. v. Ives Labs., Inc., 456 U.S. 844, 850, n.10, 214 U.S.P.Q 1, 4, n.10 (1982) (internal quotation marks omitted).

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure (the “TMEP”) explains that “[t]he functionality doctrine, which prohibits registration of functional product features, is intended to encourage legitimate competition by maintaining a proper balance between trademark law and patent law.” TMEP § 1202.02(a)(ii). This balance is maintained by requiring that protection for utilitarian product features be properly sough through a limited-duration utility patent, and not through the potentially unlimited protection of a trademark registration. See id. With the expiration of the utility patent, the invention (and its utilitarian function) enters the public domain, and others may copy the functional features disclosed in the patent. This approach encourages advances in product design and manufacture, one of the underlying purposes of patent law. Were trademark law to cover functional features, advances in product design and manufacture could by stymied by the potentially unlimited protection of a trademark registration.

B. Functionality serves as an absolute bar to registration

The determination that a proposed mark is functional constitutes, for public policy reasons, an absolute bar to registration on either the Principal or Supplemental Register, regardless of evidence showing that the proposed mark has acquired distinctiveness. See 15 U.S.C. § 1052(e)(5). In TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Marketing Displays, Inc., the Supreme Court stated that a feature is functional as a matter of law if it is “essential to the use or purpose of the article or if it affects the costs of quality of the article.” 532 U.S. 23, 33 (2001).

The burden of proof in functionality determinations, which are questions of fact, is on the Examining Attorney, who must establish a prima facie case that the proposed mark is functional in order to make and maintain the functionality refusal under Section 2(e)(5). In making such a determination, the Examining Attorney must examine the application content and must also conduct independent research to obtain evidentiary support for the refusal. TMEP § 1202.02(a)(iv). If there is reason to believe the mark may be functional but there is not enough evidence to support a functionality refusal, the Examining Attorney must issue a request for information to obtain information from the application so that an informed decision can be made and a functionality refusal be issued, if appropriate. See id. If a refusal is issued, the burden then shifts to the applicant to present competent evidence to rebut the Examining Attorney’s prima facie case of functionality. Id.

To determine functionality, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office will typically consider:

- the existence of utility patent that discloses the feature’s utilitarian advantages

- advertising by the applicant that promotes that utilitarian advantages of the design

- facts pertaining to the availability of alternative designs; and

- facts pertaining to whether the design results from a comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture. TMEP § 1202.02(a)(v).

For example, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) held the color black for packaging for floral arrangements to serve an aesthetic function in relation to floral packaging because it is associated with an elegant classic look, and is also a color to communicate grief or condolence as well as a color associated with Halloween. In Re Florists Transworld Delivery, Inc., 105 U.S.P.Q.2d 1377 (T.T.A.B. Mar. 28, 2013).

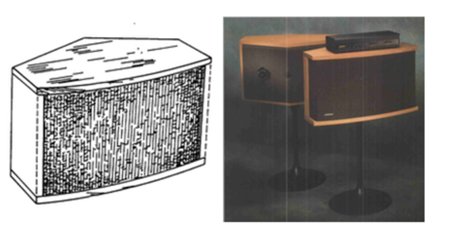

The federal court in In re Bose, 772 F.2d 866 (Fed. Cir. 2006) held that the pentagonal and curved design of a Bose speaker serves a utilitarian function. The Court found that “Bose’s utility patent, which expressly claims a loudspeaker system with angled baffles and a pentagonal cross-section provides ‘strong evidence’ of the functionality of Bose’s loudspeaker design.” Id.

C. Aesthetic functionality also serves an absolute bar to registration

Aesthetic functionality refers to situations where the feature may not provide a truly utilitarian advantage, but provides other competitive advantages, and similarly to the more traditional functionality considerations, precludes a business from monopolizing useful competitive advantages under the guise of identifying the advantage as the source of the product. After years of confusion, and some apparent rejection of the concept of aesthetic functionality, the Supreme Court in TrafFix Devices referred to aesthetic functionality as a valid legal concept. See 532 U.S. 23, 33, 58 U.S.P.Q.2d 1001, 1006. For example, the court in Deere & Co. v. Farmhand, Inc., 560 F. Supp. 85 (S.D. Iowa 1982) found the color green for John Deere forestry machines to be aesthetically functional because ‘farmers prefer to match their loaders to their tractor”. John Deere eventually registered a color combination of green and yellow to acquire some protection for its use of the color green in connection with forestry machines.

A more recent case of a court’s consideration of aesthetic functionality is Christian Louboutin S.A.’s trademark application to protect the color red as used in connection with women’s high-heeled shoes with high-gloss red lacquer soles. In its discussion of whether Christian Louboutin S.A. in entitled to trademark protection of a red-sole, the Second Circuit (a federal court) confirmed that there can be no per se rule denying protection for the use of a single color as a trademark in a particular industry – including the fashion industry, because the determination of functionality is necessarily a question of fact. See Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves St. Laurent America Holding, Inc., 696 F.3d 206 (2d Cir. 2012) citing Qualitex, 514 U.S. 159.

According to the Louboutin Court, “a single color, standing alone, could almost never be inherently distinctive because such marks do not automatically tell a customer that it refers to a brand, but rather, over time, customers come to treat a particular product color as signifying a unique source.” Christian Louboutin, 696 F.3d at 225. Therefore, secondary meaning must be analyzed. Following a consideration of whether, in the absence of inherent distinctiveness, Louboutin had achieved secondary meaning, the Court found that secondary meaning had been established only in instances where the sole contrasted with the upper part of the shoe, and not a monochromatic red shoe, including the sole. Ultimately, the Court held that Christina Louboutin’s red sole trademark is valid, but only when the red color contrasts with the color of the upper part of the shoe.

In its decision, the Court held that a mark is aesthetically functional, and therefore ineligible for trademark protection, if: (1) the design feature is essential to the use or purpose of the article, (2) the design feature affects the cost or quality of the article and (3) protecting the design feature would significantly undermine a competitor’s ability to compete. The Court issued a warning that “courts must avoid jumping to the conclusion that an aesthetic feature is functional merely because it denotes the product’s desirable source. Id. at 222.

III. ACQUIRED DISTINCTIVENESS

In additional to clearing the functionality hurdle, applicants must frequently prove acquired distinctiveness must frequently for non-traditional marks that lack inherent distinctiveness. Color marks, scent marks, three dimensional shape marks, and flavor/taste marks can never be inherently distinctive, and thus, proof of acquired distinctiveness is always required for registration on the Principal Register. Sound marks, motion marks, and touch marks could be inherently distinctive, in which case no proof of acquired distinctiveness would be required for registration.

The Lanham Act specifically provides for registration of marks that have acquired distinctiveness:

Except as expressly excluded in subsections (a), (b), (c), (d), (e)(3), and (e)(5) of this section, nothing in this chapter shall prevent the registration of a mark used by the applicant which has become distinctive of the applicant’s goods in commerce. The Director may accept as prima facie evidence that the mark has become distinctive, as used on or in connection with the applicant’s goods in commerce, proof of substantially exclusive and continuous use thereof as a mark by the applicant in commerce for the five years before the date on which the claim of distinctiveness is made. Nothing in this section shall prevent the registration of a mark which, when used on or in connection with the goods of the applicant, is primarily geographically deceptively misdescriptive of them, and which became distinctive of the applicant’s goods in commerce before December 8, 1993. 15 U.S.C. § 1052(f).

Three basic types of evidence may be used to establish acquired distinctiveness under §2(f) for a trademark or service mark:

- Prior Registrations: A claim of ownership of one or more active prior registrations on the Principal Register of the same mark for goods or services that are sufficiently similar to those identified in the pending application (37 C.F.R. § 2.41(a)(1); see TMEP §§ 1212.04–1212.04(e));

- Five Years’ Use: A verified statement that the mark has become distinctive of the applicant’s goods or services by reason of the applicant’s substantially exclusive and continuous use of the mark in commerce for the five years before the date on which the claim of distinctiveness is made (37 C.F.R. § 2.41(a)(2); see TMEP §§ 1212.05–1212.05(d)); and

- Other Evidence: Other appropriate evidence of acquired distinctiveness (37 C.F.R. § 2.41(a)(3); see TMEP §§ 1212.06–1212.06(e)(iv)).

A. Prior Registration as Proof of Distinctiveness

The Examining Attorney has the discretion to determine whether the nature of the mark sought to be registered is such that a claim of ownership of an active prior registration for sufficiently similar goods or services is enough to establish acquired distinctiveness. TMEP § 1212.04(a). For example, if the mark sought to be registered is deemed to be highly descriptive or misdescriptive of the goods or services named in the application, the Examining Attorney may require additional evidence of acquired distinctiveness. Id. citing In re Loew’s Theatres, Inc., 769 F.2d 764, 769, 226 U.S.P.Q. 865, 869 (Fed. Cir. 1985) (finding claim of ownership of a prior registration insufficient to establish acquired distinctiveness where registration was refused as primarily geographically deceptively misdescriptive).

The Examining Attorney must also determine whether the goods or services identified in the application are “sufficiently similar” to the goods or services identified in the active prior registration(s). TMEP § 1212.04(c); see also 37 C.F.R. §2.41(a)(1). If the similarity or relatedness is self-evident, the Examining attorney may generally accept the §2(f) claim without additional evidence. This is most likely to occur with ordinary consumer goods or services where the nature and function or purpose of the goods or services is commonly known and readily apparent (e.g., a prior registration for hair shampoo and new application for hair conditioner). If the similarity or relatedness of the goods or services in the application and prior registration(s) is not self-evident, the examining attorney may not accept the §2(f) claim without evidence and an explanation demonstrating the purported similarity or relatedness between the goods or services. This is likely to occur with industrial goods or services where there may in fact be a high degree of similarity or relatedness, but it would not be obvious to someone who is not an expert in the field. Id.

B. Five Years of Use as Proof of Distinctiveness

Section 2(f) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(f), provides that “proof of substantially exclusive and continuous use” of a designation “as a mark by the applicant in commerce for the five years before the date on which the claim of distinctiveness is made” may be accepted as prima facie evidence that the mark has acquired distinctiveness as used in commerce with the applicant’s goods or services. TMEP § 1212.05; see also 37 C.F.R. § 2.41(a)(2). The USPTO may, at its option, require additional evidence of distinctiveness. In re La. Fish Fry Prods., Ltd., 797 F.3d 1332, 116 U.S.P.Q.2d 1262 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (noting that the statute does not require the USPTO to accept five years’ use as prima facie evidence of acquired distinctiveness). TMEP § 1212.05.

C. Establishing Distinctiveness by Actual Evidence

An applicant may submit affidavits, declarations under 37 C.F.R. § 2.20, depositions, or other appropriate evidence showing the duration, extent, and nature of the applicant’s use of a mark in commerce that may lawfully be regulated by the U.S. Congress, advertising expenditures in connection with such use, letters, or statements from the trade and/or public, or other appropriate evidence tending to show that the mark distinguishes the goods or services. TMEP § 1212.06. The kind and amount of evidence necessary to establish that a mark has acquired distinctiveness in relation to goods or services depends on the nature of the mark and the circumstances surrounding the use of the mark in each case. Id.

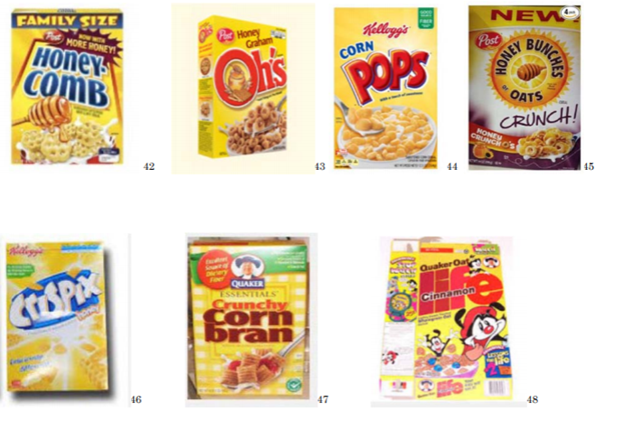

D. Example: General Mills not able to show acquired distinctiveness for color yellow

General Mills applied to protect the color yellow in connection with its Cheerios brand toroidal-shaped oat-based cereal. In affirming the refusal to register, the TTAB held that “the presence in the market of yellow-packaged cereals from various sources – even cereals that are not made of oats or are not toroidal in shape – would tend to detract from any public perception of the predominantly yellow background as a source-indicator pointing solely to Applicant.” In re General Mills IP Holdings II, LLC, Serial No. 86/757,390 (T.T.A.B. August 22, 2017). The examples of other yellow-packaged cereals considered by the TTAB in reaching its decision are below:

FORMS OF NON-TRADITIONAL MARKS

A. Color

Examples of colors that have successfully been registered as a trademark include the color brown, registered by UPS for motor vehicle transportation and delivery of personal property; a green and yellow combination, registered by John Deere for forestry machines; the color canary yellow, registered by 3M for stationary notes; and the color robin’s-egg blue, registered by Tiffany’s for goods such as boxes, bags, and catalog covers.

United Parcel Service of America, Inc.

Description of Mark: The mark consists of the color brown applied to the vehicles used in performing the services

Class 39: Motor vehicle transportation and delivery of personal property

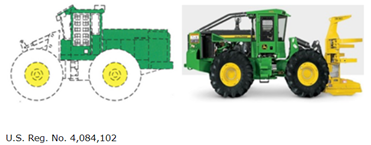

Deere & Company

Description of Mark: The mark consists of the color combination green and yellow in which green is applied to an exterior surface of the machine and yellow is applied to the wheels. The broken-line outlining is to show the position or placement of the mark on the goods. The outlining and the shape of the machine are not claimed as part of the mark.

Class 7: Forestry machines, namely, feller bunchers, skidders, harvesters, and forwarders

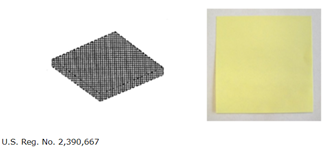

3M Company

Description of Mark: The mark consists of the color canary yellow used over the entire surface of the goods. The matter shown in broken lines shows the position of the mark and is not claimed as part of the mark.

Class 16: Stationery notes containing adhesive on one side for attachment to surfaces

Tiffany (NJ) LLC

Description of Mark: The mark consists of a shade of blue that is used on product packaging in the form of jewelry pouches with drawstrings. The broken lines depicting the jewelry pouch and drawstrings indicate placement of the mark on the product packaging and are not part of the mark.

Class 14: Jewelry

B. Scent

Examples of scents that have successfully been registered as a trademark include the scent of Play-Doh for toy modeling compounds and described as “a scent of a sweet, slightly musky, vanilla fragrance, with slight overtones of cherry, combined with the smell of a salted, wheat-based dough;” the scent inside of a Verizon store and described as “a flowery musk scent;” and the scent of bubble gum for “shoes, sandals, flip flops, and accessories, namely, flip flop bags” owned by Grendene S.A.

Scent of Play-Doh for toy modeling compounds and described as “a scent of a sweet, slightly musky, vanilla fragrance, with slight overtones of cherry, combined with the smell of a salted, wheat-based dough” U.S. Reg. No. 5,467,089

Scent of bubble gum for “shoes, sandals, flip flops, and accessories, namely, flip flop bags” U.S. Reg. No. 4,754,435

Interestingly, the Verizon scent mark is registered on the Supplemental Register because acquired distinctiveness was not shown. U.S. Reg No. 4618936. During the prosecution of this mark, the Examining Attorney held that “[p]rospective consumers are unlikely to perceive a scent as a service mark for ‘retail store services featuring communication products and services, consumer electronics, and demonstration of products’ because . . . stores commonly use scents to create ambiance in stores.”

Submitting a specimen for a scent mark requires a bit more creativity and could include sending the Examining Attorney a scented product or a vial of scent oil to demonstrate use of the mark.

C. Shape

Examples of 3-dimensional shapes that have successfully been registered as a trademark include the shape of Lego brand toys figures, the contour of a Coca-Cola bottle, the shape of a Toblerone candy bar, and the shape of Pez candy.

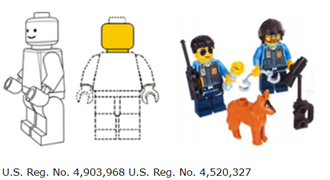

LEGO Juris A/S

Description of Mark: The mark consists of the three-dimensional configuration of a toy figure featuring a cylindrical head, on top of a cylindrical neck, on top of a trapezoidal torso of uniform thickness, with flat sides and a flat back, where arms are mounted slightly below the upper surface of the torso, on top of a rectangular plate, on top of legs of legs which bulge frontwards at the top and are otherwise rectangular with uniform thickness, on top of flat square feet.

Description of Mark: The mark consists of a 3-dimensional configuration of a cylindrical yellow toy figure head, on top of a yellow cylindrical neck. The dots outlining the toy figure show the placement of the mark on the goods and are not part of the mark.

Class 28: Toy figures; play figures; positionable toy figures; modeled plastic toy figurines; three dimensional positionable toy figures sold as a unit with other toys; construction toys; toy construction set

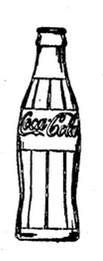

Description of Mark: The trademark consists of the distinctively shaped contour, or confirmation, and design of the bottle as shown

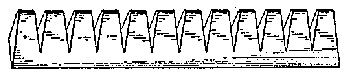

Description of Mark: The mark is a configuration of the goods. The mark consists of a symmetrical candy brick having two faces, an obverse face and a reverse face, wherein the two faces are each surrounded on the periphery by a common, unitary wall in the shape of a race track, wherein the two faces of the brick each form a rectangular recess below the edge of the common, unitary wall and wherein the name “PEZ” appears prominently on each recessed face. The dotted lines indicate placement of the lettering “PEZ” on the candy piece. The lettering “PEZ” is not part of the mark.

D. Flavor

While trademark protection for a flavor is technically fathomable, realistically, it would very unlikely. There are currently no registered flavor trademarks and TTAB and federal courts have consistently held against affording trademark protection to flavors.

Products made for human consumption, such as foods and beverages, which have a pleasing taste would likely be disqualified from protecting the flavor or taste based on the functionality doctrine. In In re N.V. Organon, for example, the TTAB denied a pharmaceutical company a trademark in the orange flavor of its pills on functionality grounds. The TTAB explained that because medicine generally has “a disagreeable taste” flavoring medicine serves a “utilitarian function that cannot be monopolized without hindering competition in the pharmaceutical trade.”

If a product were not made for human consumption and for some reason had a flavor, that product would be a more likely candidate for trademark protection because it could overcome the functionality hurdle.

E. Sound

Examples of sound trademarks that have successfully been registered include chimes for NBC entertainment services (U.S. Reg. No. 916,522); drums, trumpets, and strings for Twentieth Century Fox entertainment services and motion picture films (U.S. Reg. No. 2,000,732); duck quacking the word “AFLAC” for American Family Life Assurance insurance services (U.S. Reg. No. 2,607,415); and Homer Simpson saying “D’OH” for Twentieth Century Fox for entertainment services (U.S. Reg. No. 3,411,881).

F. Motion

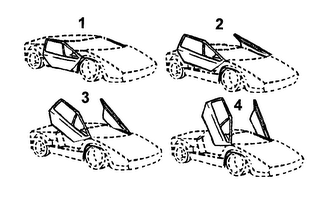

Examples of motion trademarks that successfully been registered as a trademark include the motion in which the door of a vehicle is opened, owned by Automobil Lamborghini S.p.A. and registered on the Principal Register with a successful claim of acquired distinctiveness; the motion of a three dimensional spray of water issuing from the rear of jet propelled watercraft, owned by Yamaha Hatsudoki Kabushiki Kaisha and registered on the Principal Register with a successful claim of acquired distinctiveness; and the live visual and motion elements of The Peabody Duck March as performed at The Peabody Hotels, also registered on the Principal Register.

Description of Mark: The mark consists of the unique motion in which the door of a vehicle is opened. The doors move parallel to the body of the vehicle but are gradually raised above the vehicle to a parallel position.

Description of Mark: The mark is comprised of a three dimensional spray of water issuing from the rear of a jet propelled watercraft and is generated during the operation of the watercraft.

Description of Mark: The mark consists of the live visual and motion elements of the The Peabody Duck March as performed at The Peabody Hotels, only one segment of which is depicted in line art in the drawing. The motion elements include the red carpet being rolled out, the appearance of the ducks and uniformed Duckmaster at the elevator door, and the march of the ducks down the red carpet, up the steps, and into the fountain where they begin swimming. The mark also includes the fanfare in reverse sequence.

G. Touch/Texture

Fresh Inc. owns a registration for cotton-texture paper wrapped around oval-shaped soap and tied with a silver-colored wire that is coiled around and fastened to a semi-precious stone bead. While this is not exclusively a texture trademark, the cotton-textured paper is protected by the registration.

Description of Mark: The mark consists of cotton-textured paper wrapped around oval-shaped soap and tied with a silver-colored wire that is coiled around and fastened to a semi-precious stone bead.

The David Family Group LLC owns a registration for a leather texture wrapping around the middle surface of a bottle of wine.

Description of Mark: The mark consists of a leather texture wrapping around the middle surface of a bottle of wine. The mark is a sensory, touch mark.