By Julia Belagorudsky

Shannon DeVivo v. Celeste Ortiz, ___ U.S.P.Q. 2d. ____(T.T.A.B., March 11, 2020)

The title of a single book cannot be registered as a trademark in the United States, but a March 11, 2020, precedential decision of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board holds that other uses of the title, such as in a design on the book itself or a companion website, can be considered trademark use. Therefore, use of a mark in a book title is not a death knell for trademark registration if the mark is also used in a separate source-indicating manner.

In Shannon DeVivo v. Celeste Ortiz, Celeste Ortiz (“Ortiz”) filed an application on November 18, 2017, to register the word mark ENGIRLNEER, based on intent to use, for “cups, coffee cups, tea cups and mugs” in Class 21, “lanyards for holding badges; lanyards for holding keys” in Class 22, and “hoodies, shirts, sweatshirts” in Class 25. Shannon DeVivo (”DeVivo”) filed a Notice of Opposition, asserting that she had developed common law rights in the mark ENGIRLNEER for providing information to young women and girls seeking careers in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math (“STEM”) and that Applicant’s mark ENGIRLNEER was likely to be confused with hers for the asserted services. In sustaining the opposition, the Board considered whether DeVivo’s mark was used in connection with the stated services, and whether such use served a source-indicating function.

DeVivo’s Use of ENGIRLNEER as a Source Indicator for the Asserted Services

To support her assertion of common law rights, DeVivo alleged that she had continuously used the mark ENGIRLNEER since at least October 23, 2017, in connection with providing information services to young women and girls seeking careers in STEM fields; providing a website featuring educational information in STEM fields for young women and girls pursuing a career in these fields; and providing online non-downloadable educational information in STEM fields. DeVivo also asserted that since at least November 11, 2017, she had continuously used the mark ENGIRLNEER in commerce in connection with books.

In detailing her specific use of the mark ENGIRLNEER, Devivo stated in her Testimonial Declaration that she coined the term ENGIRLNEER in the first part of 2017; that she registered engirlneer.com as a domain name in approximately June 2017, that she started publishing information on her website at www.engirlneer.com in September 2017; that the ENGIRLNEER mark is prominently featured in large lettering centered on the top of every page of her website; and that since the launch of the website and her first book, she had regularly spoken at events for school-aged children where she promoted ENGIRLNEER books, informational services, and her website.

DeVivo additionally stated that by October 30, 2017, she had used the mark ENGIRLNEER on her website in connection with a full cast of fictional characters, “the Engirlneers,” to introduce girls to STEM careers and teach them about real-world problems in a variety of STEM-related areas such as chemistry, geology, biology and animals, traffic safety, and water supply. By November 11, 2017, DeVivo had added information to her website, including a downloadable book featuring the fictional characters that introduced girls to phosphates and how they enter ponds and streams. Users were able to freely download a full copy of the book, and by January 2018, DeVivo’s books were available on Amazon.com.

DeVivo submitted copies of her website on various dates in order to prove her prior use and to illustrate the nature of her use of the mark ENGIRLNEER:

Another image of DeVivo’s website showed an introduction to the characters “Elan” and “Betty,” with descriptions of their interests in STEM topics, such as water supply and wildlife.

In response to this evidence, Ortiz argued that the brief character descriptions (like those for Elan and Betty) were not directly linked to “providing career information” and that students who are mature enough to make career choices would not be interested in children’s books. The Board dismissed these arguments as unsupported speculation.

DeVivo also submitted an image from the website featuring the book:

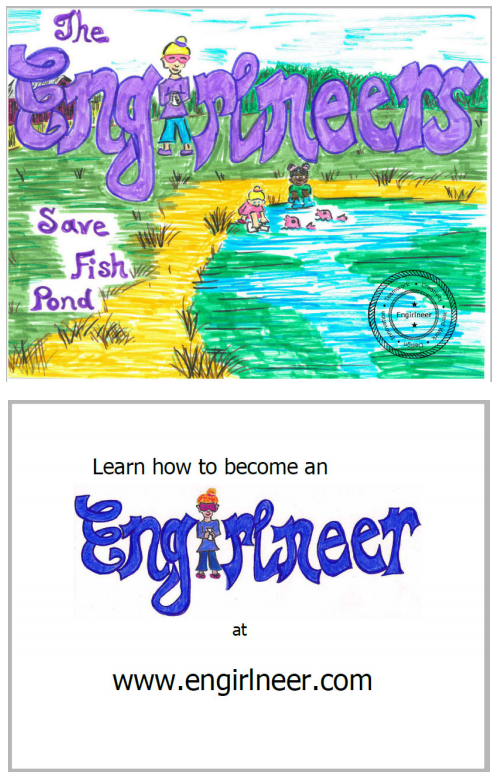

The first two pages of DeVivo’s book, The Engirlneers Save Fish Pond, showed the mark ENGIRLNEER used in the following manner:

The last page of the book included a “seal design” that used the mark ENGIRLNEER in the center, with the words “Teamwork ∙ Creativity ∙ Hard Work ∙ Design ∙ Innovation” forming a circle around ENGIRLNEER (this seal is also used on the front cover), on an otherwise blank page:

In its consideration of DeVivo’s evidence, the Board held that her maintenance of, and updates to, her webpages with the character descriptions, the downloadable book, and the assertions in the Testimonial Declaration established that she had used the mark ENGIRLNEER in connection with the asserted services.

DeVivo’s Use of ENGIRLNEER as a Source Indicator for Books

DeVivo claimed that the mark ENGIRLNEER is used as a source indicator in at least three places on the The Engirlneers Save Fish Pond book:

- In the bottom right corner on the front cover of the book, ENGIRLNEER is used as part of the seal, separate and apart from the book’s title;

- on the second page of the book, in large blue lettering; and

- on the last page, where the seal appears again, on an otherwise blank page.

In response to this assertion, Ortiz argued that the seal design could not function as a trademark because it was a laudatory self-approval seal that was “masquerading as a third-party seal of approval.” (Applicant’s brief at p. 21). The board disagreed, finding that the wording in the seal suggested the qualities of an engineer, and there was nothing in the seal to suggest it was a third-party seal of approval.

The Board stated that for ENGIRLNEER in the seal design to function as a source indicator for books, it must not function “merely as part of the title of the book or the name of a character in the book.” DeVivo v. Ortiz, p. 22. It reasoned that a publisher’s mark such as the term ENGIRLNEER located within the seal design may serve as more than just the identifier for a children’s book, it may also serve to inform the public that the subject matter is of a certain quality and suitability.

The Board also explained that while the book does not directly refer to any of the characters as “engirlneers,” the title makes clear that the characters are “engirlneers” and one of the pages of DeVivo’s website reinforces this association by depicting images and names of the characters under the heading “The Engirlneers.”

Ultimately, even though ENGIRLNEERS appears as the title of the book and is the group name for the characters in the book, the positioning of the term distant from the title of the book in the seal on the front cover, its inclusion within a design, its prominent size, its appearance on the second page of the book in conjunction with an invitation to the reader to “learn how to become an engirlneer,” and its appearance on the last page of the book, result in separate and distinct commercial impressions of use as a mark for DeVivo’s book.

Having established DeVivo’s priority of use for her mark ENGIRLNEER, the Board finally considered the likelihood of confusion with Ortiz’s mark. In finding that the parties’ goods and services were related, the Board concluded that sweatshirts and shirts, cups and mugs, and lanyards for holding badges and keys were all commercially related to books, as was the provision of educational and professional information in the STEM fields). The Board relied, at least in part, on DeVivo’s evidence of third-party registrations that identified both children’s books and clothing. The Board therefore sustained DeVivo’s opposition and refused registration to Ortiz’s ENGIRLNEER mark.