By Sahil Yadav

The EU General Court recently confirmed the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO)’s decision to invalidate the trademark registration of the well-known and popular Rubik’s Cube pursuant to a decision by the Court of Justice of the European Union (“ECJ”) that it was not registrable as a trademark under Article 7(1)(e)(ii) because the shape of the mark involves a technical function. The ECJ’s decision was reported by us earlier here.

Background and Procedural History

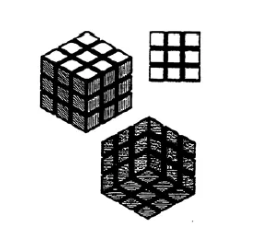

Rubik’s Brands Ltd. (“Rubik’s Brands”) owns rights to the Rubik’s Cube and in 1999 obtained EUTM Reg. No. 162784 for a three-dimensional mark for “three-dimensional puzzles” depicted as follows (“the Rubik’s Cube mark”):

In 2006, Simba Toys GmbH & Co. (“Simba Toys”), a German toy manufacturer, filed a request for a declaration of invalidity of the Rubik’s Cube mark. Simba Toys alleged that the Rubik’s Cube mark consisted of a shape that is necessary to obtain a technical result (i.e., the rotating capability of the cube) and thus should not be registrable as a trademark. The Cancellation Division of the EUIPO rejected Simba Toys’ application for a declaration of invalidity and the Board of Appeals dismissed Simba Toys’ appeal of that decision. Simba Toys subsequently brought an action in the EU General Court seeking annulment of the appellate decision, but in 2014 the EU General Court also upheld the validity of the Rubik’s Cube mark. Simba Toys then appealed the EU General Court’s decision to the ECJ which agreed with Simba Toys and held the Rubik’s Cube mark to be unregistrable. Pursuant to this decision by the ECJ, the Cancellation Division of the EUIPO invalidated the Rubik’s Cube mark. Rubik’s Brands then challenged the EUIPO’s decision to invalidate the Rubik’s Cube mark at the EU General Court, which has now confirmed the invalidation decision.

EU General Court’s Decision

Rubik’s Brands raised four grounds of appeal. Its first and main ground of appeal was that the EUIPO did not correctly identify the essential characteristics of the contested mark and that it also incorrectly assessed the functionality of the essential characteristics identified by it.

For the relevant test, the EU General Court relied upon the decision in Lego Juris v. OHIM, C-48/09 P. This case established that the identification of the essential characteristics may be carried out by means of a simple visual analysis of the sign, or a detailed assessment, taking into account relevant criteria such as survey evidence, expert opinions and data relating to earlier intellectual property rights. Next, the competent authority must ascertain whether the essential characteristics perform a technical function with regard to the goods at issue. This may include consideration of information relating to previous patents, where applicable.

The EU General Court found that the EUIPO erred in identifying the essential characteristics of the Rubik’s Cube mark by including “the differences in the colors on the six faces of the cube.” It also observed that it is not possible to detect, from a simple visual analysis of the graphic representation of the mark, the presence of color variations. In addition, Rubik’s Brand Ltd did not claim any color indications or references to such in the mark description. Indeed, the Court asked the parties at the oral hearing whether they considered the color variations to be an essential feature of the Rubik’s Cube mark and the parties agreed that it did not.

Despite acknowledging the EUIPO’s error in identifying one of the essential characteristics of the Rubik’s Cube mark, the EU General Court upheld the EUIPO’s decision of invalidaty since it found that the other essential characteristics of the Rubik’s Cube (which were correctly identified by the EUIPO), namely, the grid structure formed by the black lines on each face of the cube and its cube shape, to be functional in nature and intended to obtain a technical result. Full decision available here.

Comments

The EU General Court’s decision confirms the line drawn by the ECJ between protectable subject matter under trademark law and patent law. It is a sensitive issue since owners of many innovative products attempt to protect their designs through trademark, where rights are perpetual as long as the mark is in use, once its limited-time patent rights are exhausted.

The gist of Rubik’s Brands arguments was based on design freedom, i.e., the essential visual features of the Rubik’s Cube are not functional in nature since a puzzle cube can also be constructed without incorporating Rubik’s Cube’s specific visual elements and that third-parties are free to construct their owns puzzle cubes without these visual elements. For example, a puzzle cube may be in the shape of a three-dimensional hexagon instead of a cube or its grid structure may be of a color other than black. The decision confirms that design freedom is irrelevant when assessing the functionality of essential characteristics of a three-dimensional trademark.

While it may seem like this is the end of the road for Rubik’s Brands when it comes to protecting the design of the Rubik’s Cube, it still has the right to appeal the EU General Court’s decision to the ECJ and it remains to be seen whether it will do so. Outside of the EU, Rubik’s Brands continues to persevere with its efforts to protect the design in the Rubik’s Cube through trademark rights. For instance, in India, the Delhi High Court recognized trademark rights in the Rubik’s Cube mark and granted Seven Towns (Rubik’s Brands’ parent company) a temporary injunction against a third party manufacturing a near-identical puzzle cube under the RANCHO’S CUBE mark. Full decision here.